One of Nerdguy's many peculiar pasts was working in theater. In high school, I joined and ultimately ran the theater for two years. After college, I worked another three years in the theater scene that presaged the Seattle Fringe theater movement. Then, finally, after my bicycle trip around the world, I spent six more years working in the IT department for Seattle Opera.

Scale

Our budget for a major high school production ran approximately $250. The wonders of all volunteer labor. In the early 1980s Seattle pre-Fringe era, mounts (new productions) ran between $1,000 and $10,000, including crazy cheap labor and hungry actors.

A typical opera production in the late-1990s when I was there had a budget of a couple million. A big, new production might run as high as $5M.

In 1983, we took over an old porn house, gutted it, steam-cleaned and painted the seats, rebuilt the stage, painted all of the walls, hung new lighting instruments, and I installed a large new lighting and sound system, all for about $30,000 and it took us a week.

In 2003, McCaw Hall reopened after a year-long, $127M renovation that I had a very tiny part in. I left the opera in 2001, so my role never had a chance to get bigger. Would have been fun, though, now that I think about it. Nerding out over an entire new building on that scale....whoo-whee!

On last piece on scale:

- Typical high school production: 6 weeks prep and rehearsal, 700-seat auditorium, 3 performances

- The typical Seattle theater production I was involved in: 6 weeks prep and rehearsal (with some planning before that), 1-200 seat house, 700 performances (6 shows a week). (That's how many I did on Angry Housewives, it ran closer to 6,000 total performances.)

- The typical opera production: 1-2 years of prep (planning before that), 3,000-seat hall, 8 performances.

The Hall

Inside the shell of the White House, May 1950

McCaw Hall began life as an Armory. Then in 1928 it was turned into Civic Auditorium. A major renovation was done in preparation for the first World's Fair after WWII in 1962. Part of the renovation gutted the interior and built a whole new building inside the armory (much as the Truman renovation built a whole new White House inside the old White House). It made for a fascinating set of curious backstage passages in the gaps, to say the least.

One of the peculiar shortcomings of the Opera House during the years I worked there was the area above the stage--the Fly Loft.

My high school theater's loft, rose perhaps fifteen feet above the stage. Just enough to hide the above stage lights behind some long, short curtains called teasers. In the small Seattle theaters, there was no loft. There were exposed pipes bolted to the ceiling from which we hung lighting instruments and not much else.

Mostly set up in old warehouse spaces, our problems were more that the audience in the back row of seats might risk hitting their heads on the ceiling.

Seattle Opera's Fly Loft was about the same height above the stage as the stage itself. That meant that if we wanted to raise a long drape out of view, we could--barely. But then it's bottom edge was interfering with lights, other set pieces, and...let's just say that it was problematic.

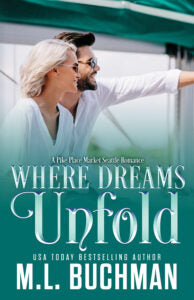

Then came the McCaw Hall renovation. I had travelled back to Seattle to have a friend who still worked there give me a tour so that I could write my 2014 book Where Dreams Unfold that is partly set there as it is a romance centered around an opera production.

Dramatic new seating. Lovely new acoustics (the soundman in me really appreciated it as there'd been a dead spot where the singer's voices mostly skipped the most expensive seats from about Row 8-18 of the main floor).

There were also new rehearsal spaces, dressing rooms, orchestra pit, trap doors in the stage floor itself for descents into "basements," and a hundred other fun innovations.

But the Fly Loft? Man, that was breathtaking. The stage itself was now in an 11-story high building all of its own, that just happened to open onto the beautiful, acoustically lovely seating of McCaw Hall.

The Wonder of a Fly Loft

The McCaw Hall loft.

Even in this wide-sweeping photo, it's mostly out of sight above. A few set pieces are scattered about a bare stage. Four "trees" of lighting offer side-lighting positions. The seating can be glimpsed at the very right, past the edge of the proscenium (perimeter of the stage opening). And up above are the bottoms of various drapes, some lighting instrument pipes, and the white strip is the bottom border of a 64' x 36' rear projection screen. The main drape is somewhere up there as well. For more on this, check out the technical information brochure for renters HERE.

If you ever wondered how they change scenes so quickly, sometimes in the heart of a fifteen-second blackout, that's the secret. In an instant, whole set looks can be whisked aloft and others lowered in the places. Roll out a cart, some stairs, a dragon, and the scene moves on. With the long minutes during an intermission?

The entire physical layout of walls, stairwells, ocean bottoms, lofty peaks, and trees may be switched out. And much of that happens upward, not side to side.

Below is a side view. All that the audience sees is that little bracketed area in the lower center marked The Proscenium.

There are 112 80-foot long pipes (the diagram is wrong and says lines) that are hung on six-inch centers. They're controlled by ropes that go up from the pipes to pass through a massive gridiron "the grid" of supports. The ropes then travel over pulleys to one side of the stage where they gather together and turn to go down again to the Flyloft. This is where each individual pipe is separately controlled to raise and lower the appropriate scene element. Each pipe can carry thousands of pounds of equipment or set pieces. During a major production, there may be an entire crew sitting thirty-feet above the stage in flyloft (basically bored out of their skulls--I speak from experience), awaiting their moments of mayhem as the ropes fly into action.

Overall, it's an amazing system, still closely related to my long-ago high school theater, and equal to any world-class stage in operation. But why was this Nerdguy worthy? Note the funny little gap between the gridiron and the roof at the top of the overall Fly Loft itself?

Then read the excerpt below from my upcoming novel White Top.